Flip and File

What needs kept, and how do we keep it?

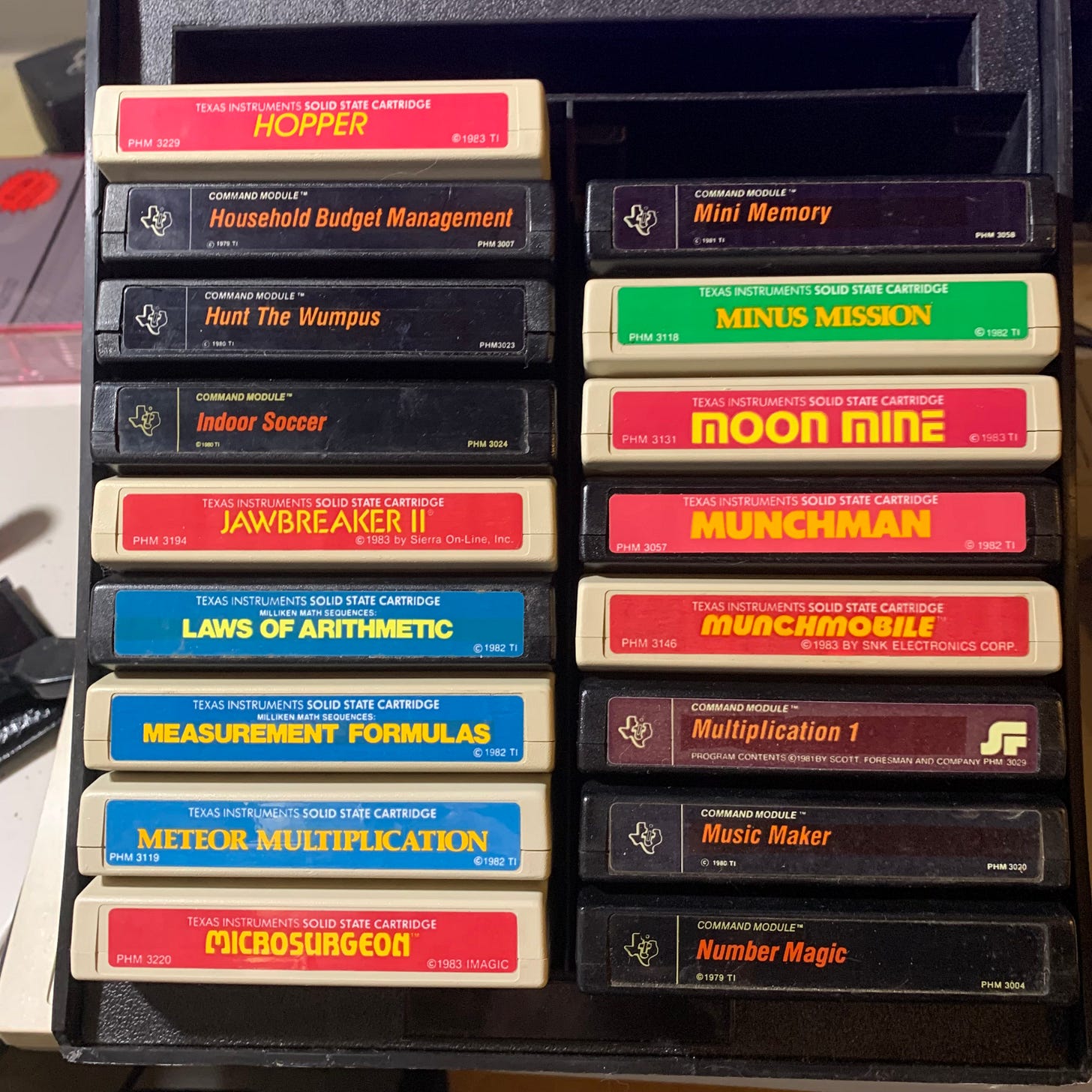

This weekend it was time to get granular down in the War Room. I have eight Flip ‘n File cartridge holders set aside, shelf space to keep them on, and no real organizational system for my cartridge collection. I brewed a pot of coffee and headed downstairs with my laptop under my arm, ready to finally knock out this chore once and for all, bring order to one more corner of my space, and set the database-ification of the rest of the Texas Instruments station in motion.

You need the Flip ‘n File holders, see, because TI cartridges have a unique shape. They’re wider than Atari carts, and have a raised front section, so that only half the cart slides into the slot on the console. Some have a tapered, extended front end, like the ones sold by Romox and Navarone, and others, like Atarisoft and Parker Brothers, employed their own unique front-end shell shapes. You can stick one TI cartridge into, say, an audio cassette holder, but the front end will block access to the spaces above and below it, making for an inefficient rack.

But these are made for the job! So let’s go.

I started on the right hand side, with the homebrew cartridges – easy. I don’t have as many of these as I’d like, but I got a bunch in a bulk buy a couple years ago, so my copies of Never-Lander, Tex Turbo, and Road Hunter/TI Scramble/Titanium are proudly displayed and catalogued. Down on this side will also live the third-party cartridges I own – games that came along in the mid-to-late 80s, mostly after the 99/4A was discontinued. Junkman Junior, Star Trap, Ant Eater, and Computer War all live in this section.

[I could just be making these names up and almost none of you would know!]

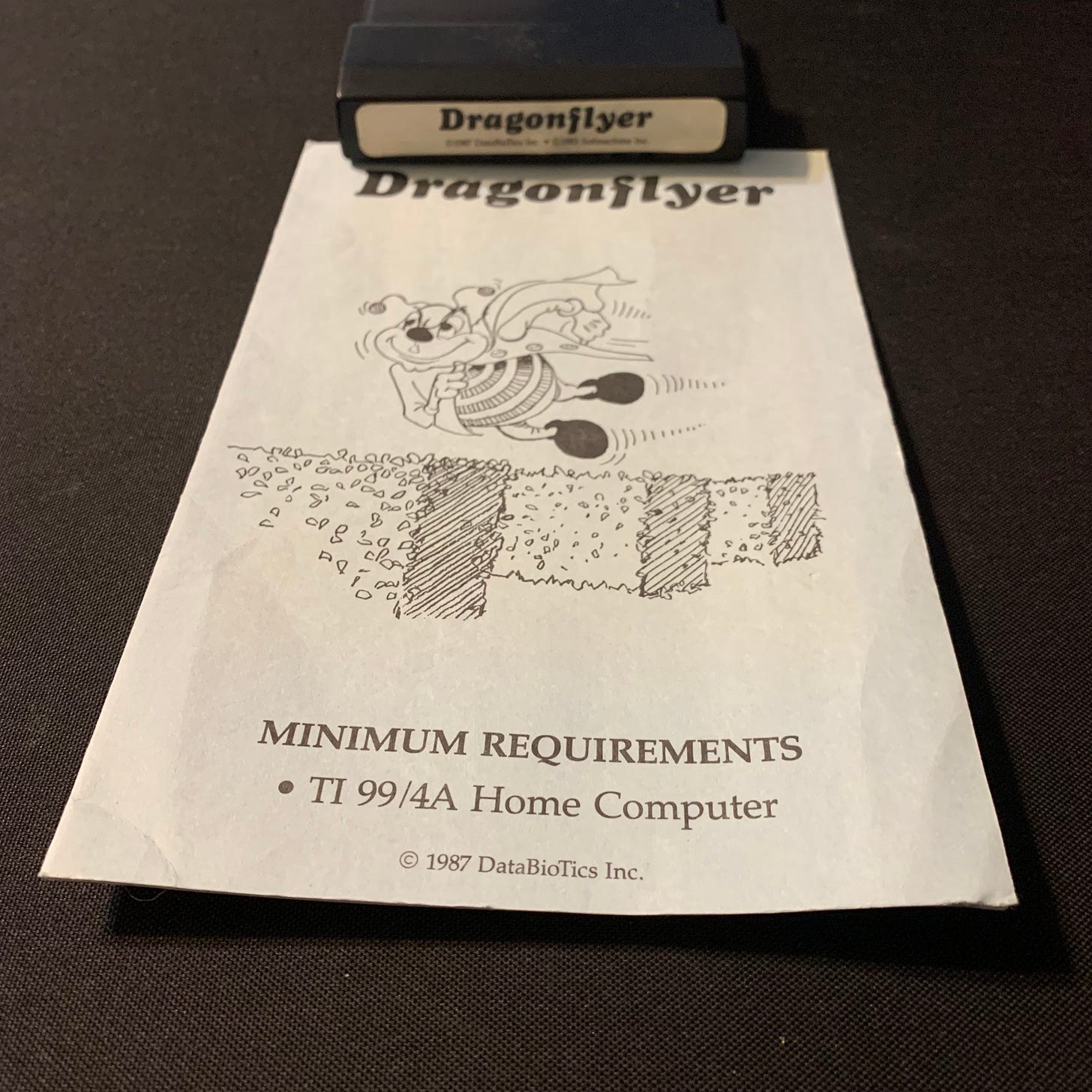

But hold on. Don’t I have a copy of Dragonflyer around here? There it is, buried in a pile of plastic-bagged cassettes with photocopied manuals.

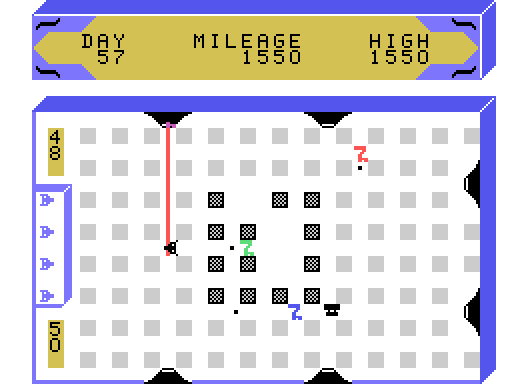

Released in 1987 in this incarnation, and also sold as “Spot Shot” at some point, Dragonflyer is one of the fastest, most awesome arcade originals of the golden age. Being sold in small quantities to a dwindling user base, there was no chance it’d get a full color box and glossy manual. It showed up from the mailorder house in a Ziploc bag, with a black-and-white folded pamphlet, and – if you were lucky – a pro-printed front label stuck on what was likely a repurposed TI cartridge shell from some overstocked educational cartridge.

Now comes the real tough part. I have to go through the stacks of TI software released by Texas Instruments, and make some decisions. Most of these titles are in flat boxes in a closet on the other side of the basement, in my store inventory, but now that I’m in archival mode, it’s time to set aside actual “collection” copies.

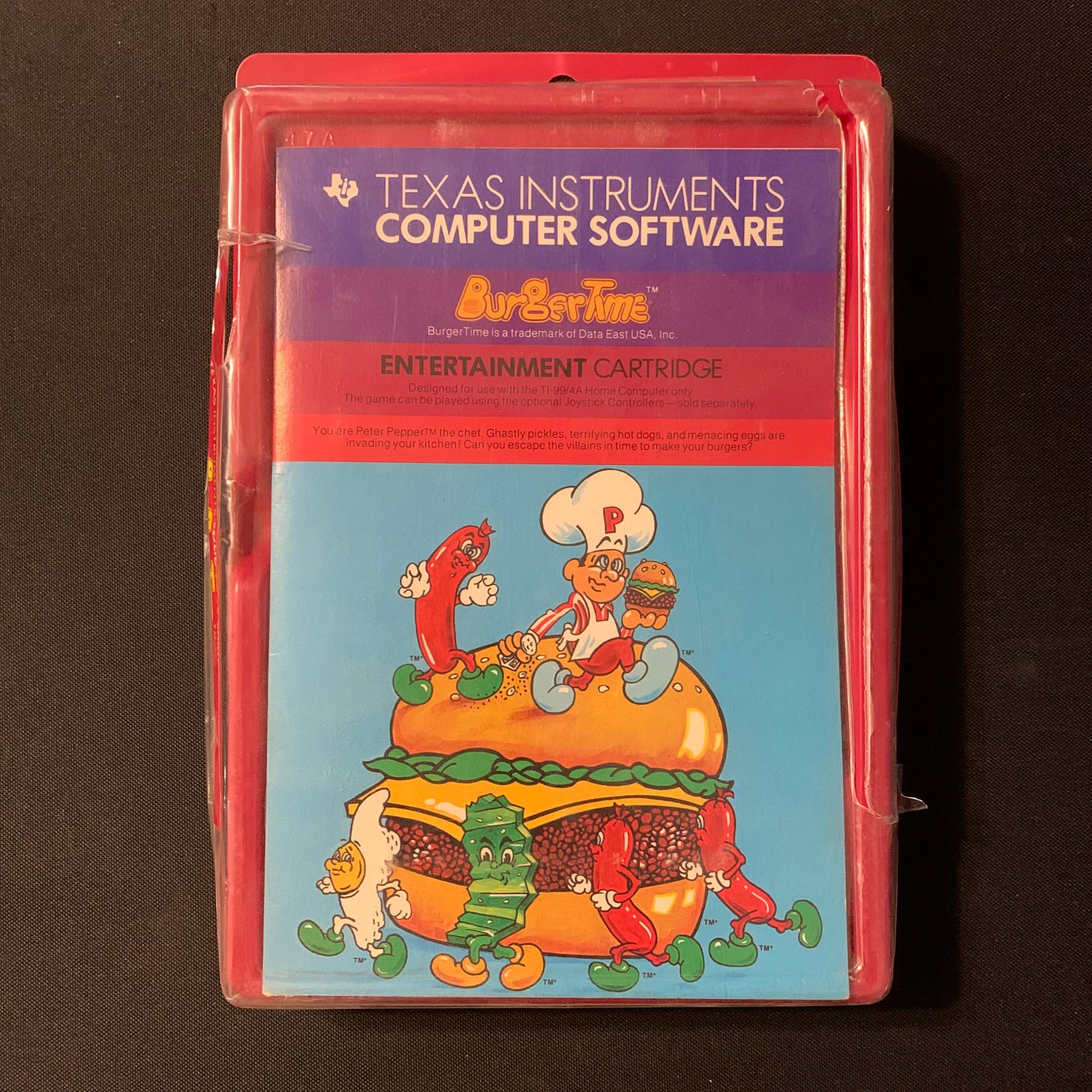

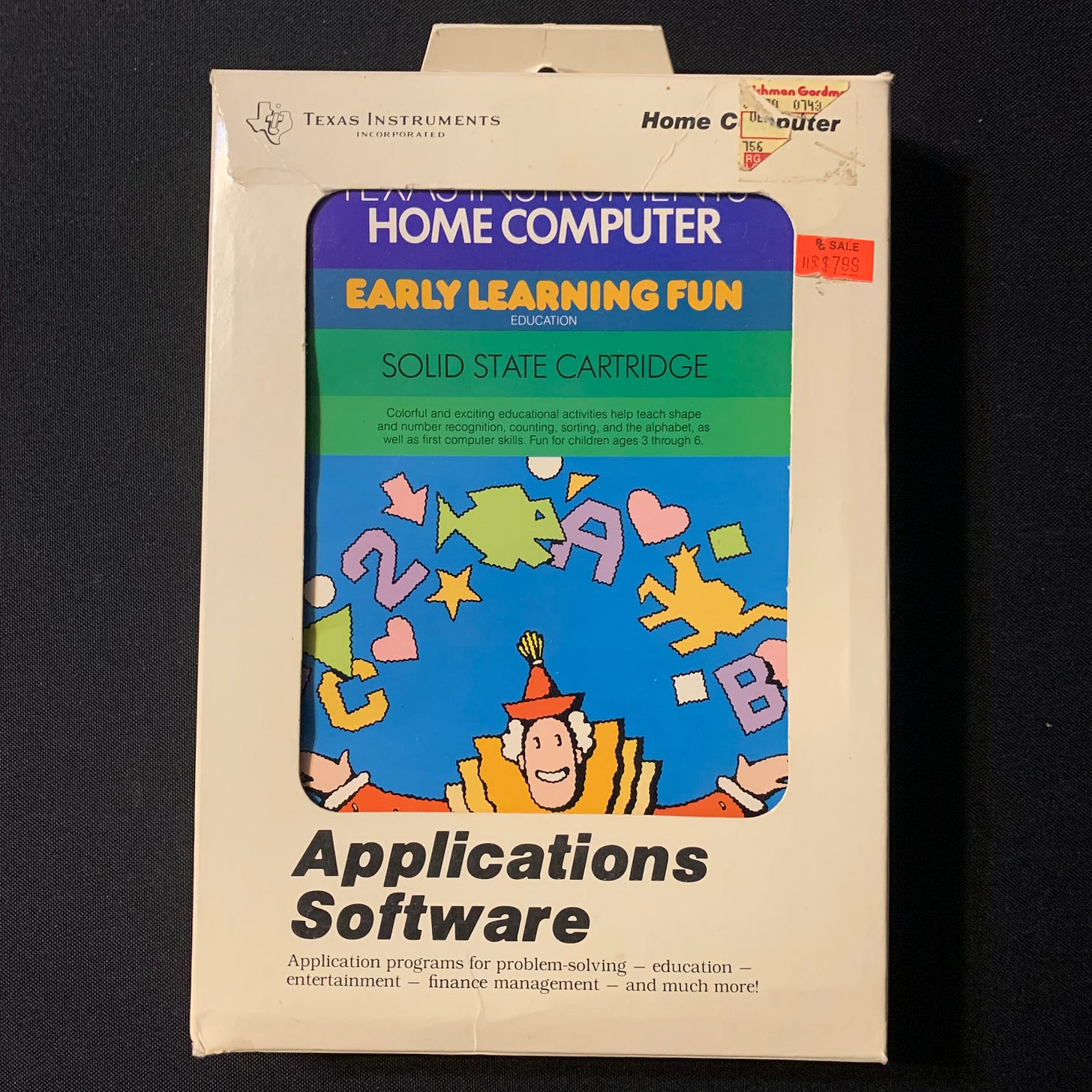

Very little of my cartridge collection for this platform is boxed, because TI’s boxes were, to put it mildly, terrible. For most of the computer’s lifespan, they were generic white cardboard with plastic inner trays that never wanted to slide out properly. The boxes had a die-cut front window to display the manual cover art, but nothing on the side to differentiate them from each other, so a shelf full of boxed carts is either a generic white blosh or a series of hand-lettered, written-on spines.

Toward the end, they did a full redesign of most of the manual covers, and switched up the shells and end labels on the cartridges, so if you want to own, say, TI Invaders, you have the 1981 manual art and black label, the much more elaborate ’83 art and big yellow letters on a red background on a white cartridge. To top it off, some later titles like Microsurgeon and Super Demon Attack were released with the same plastic inner tray covered by a flimsy plastic outer lid, often with a label on the spine. These not only cracked and broke almost immediately, but they were even less stackable than the cardboard boxes.

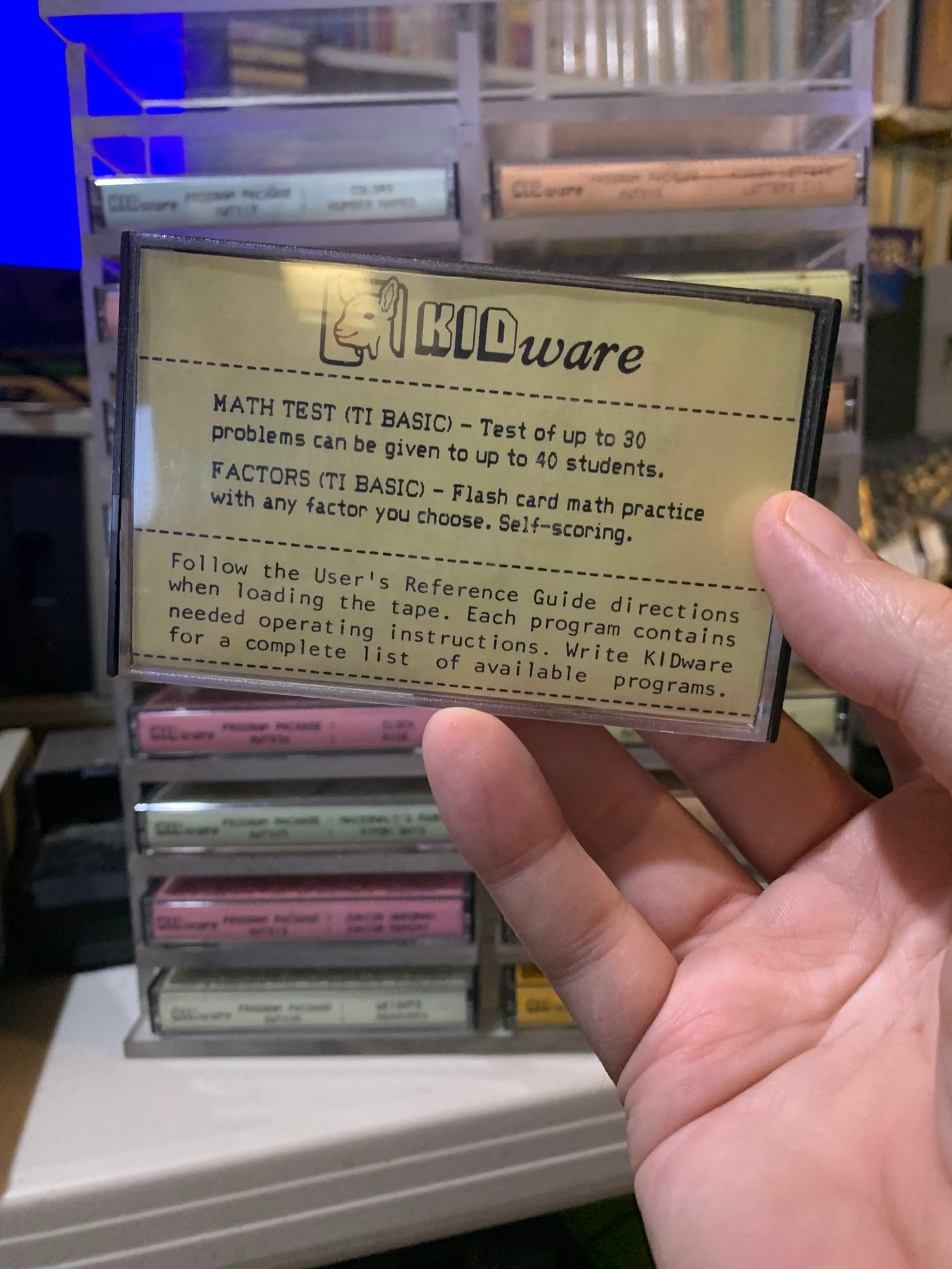

And if your eyes haven’t glazed over yet, consider that for every cartridge the average person might still pluck from the Flip ‘n File and actually use – mostly games – there are scads of educational programs for small children, utilities rendered obsolete by time, and productivity titles that ended up liquidated for pennies on the dollar in the big industry crash of ’83-’84 and are now chiefly worth cannibalizing to use their shells for homebrews.

So somewhere between “put all this stuff out on the curb” and “own both label variants of Home Financial Decisions” is where I have to set the ground rules. In the past, cash ruled everything, and oftentimes I viewed my personal collection as a lending library. If I had a rare game, I’d put it up for sale, and enjoy it while it was here, knowing when the time came, I was going to need that $75 more than I needed that game. And some titles are so plentiful, I’ve always had half a dozen sitting on the sale shelf, so I was never deprived of a game of Parsec or Chisholm Trail (the underrated but somewhat confusing successor to 1981’s Tombstone City, of course) when I wanted to play.

Now that the wolf isn’t quite as insistent at the door, I can look at, say, 1980’s Weight Control and Nutrition cartridge, marvel at it briefly as an artifact, and then decide – keep or sell? Am I in it to win it or not? Will the serotonin rush I get from walking into the War Room and seeing this phalanx of TI carts be worth the space I’m using up for something I’ll likely never plug into an actual computer and look at again, much less fathom any practical use for?

I’m starting to think in terms larger than myself as I wade through the process of cataloguing it all. I still have no idea how it would manifest, but I love the idea of this all eventually being an accessible collection, either in a brick-and-mortar museum, or some sort of library. I confess that if this idea ever comes to fruition, it may be so I can create my final masterpiece, a fifteen-foot wall of shallow ledge shelving to finally, once and for all, display every TI cartridge, cumbersome cardboard or plastic box and all, in the order of their release, tastefully lit and adorned with informational placards and QR code-activated audio lectures from your smartphone.

Until that day comes, I’ve decided that the War Room ground rules dictate the following: we save one of each cartridge, no matter how useless, but we don’t worry about label variants, and we content ourselves with carts in the Flip ‘n File, manuals in the file cabinet upstairs (already alphabetized in tabbed hanging folders in their own drawer, thank you very much). If we’ve somehow managed to find, say, a Burger Time box not caved in by forty years of indifferent attic storage, we save it in a place of honor. If we find this one instead, we keep it till we find a better one.

And now, finally, years into this experiment, I move forward. This is just the cartridges. I still have tapes, disks, and books to sort, doubles to piece out and sell, and now, easy access to all the titles I don’t have, so I can redouble my efforts to buy up collections and start filling in gaps. This will always be a work in progress, but it’s only lately that the word “progress” has actually meant something.